Sonya Manchanda Peres

On Nepal: Fieldwork Reflections

Sunset over Kathmandu, 20th April 2019

On Being Indian

I did not expect to learn as much about myself as I did on a field trip to Nepal. Although I expected I would better understand my positionality as young, educated, Western woman, the field trip uncovered more subtle elements of my positionality and encouraged me to reflect on those aspects of my identity that I have struggled with for years, while simultaneously offering validation.

1. Firstly, over the past 5 months, I have learned about India’s relationship to Nepal.

During lectures in Edinburgh, our instructors on Nepali language and culture, Mona and Radha Adhikari, verbalized dislike of India’s hegemonic soft power and level of influence within Nepal and South Asia.

I read various articles describing India and Nepal’s relationship, highlighting power imbalance between the two countries in terms of trade and resources, and incessant meddling in Nepali politics from India, creating anti-Indian sentiment and a strong desire to shape a distinct identity and nationality (Shukla, 2006).

A full three months of understanding the pain India has inflicted on Nepal.

Despite this understanding, my brain subconsciously compared almost everything to India.

Even before we arrived in Nepal, I began observing the country from the eyes of an Indian- I saw (although somewhat incorrectly) sameness in religion, geography and language and forcefully attached myself to this perceived similarity. I helped colleagues pronounce the hard “th” sound, ubiquitous in South Asian languages. I answered questions about how to eat with one’s hand.

As soon as we arrived in Kathmandu, the infrastructure and the road signs in the familiar Devanagari script reminded me of my home in India. I longed to take a train journey to Bangalore. I messaged my grandmother incessantly.

Truck with Devanagari Script in Dhulikel, 18th April, 2019

It was not until the third day of our field trip with Clare Barnes, a lecturer, and Meg Todd, a colleague, upon interaction on the patio of our bed and breakfast, The Yellow House, that I knew I needed to confront this lens and look at Nepal separately from my experiences in India. Meg and I asked Clare how she thought Kathmandu could be compared to New Delhi- India’s capital; we began discussing Nepali identity as a small nation in between India and China, two vast nations, and the external influence to which it is vulnerable. Looking back, it is funny and beautiful how a simple question and a twenty- minute conversation could trigger in me something so significant.

Me and Megan Todd in Dhulikhel, Nepal by Rosanna Harvey-Crawford, 18th April, 2019

Me and Megan Todd in Dhulikhel, Nepal by Rosanna Harvey-Crawford, 18th April, 2019

2. I am hyperaware of colonial legacies, white supremacy and structural injustices. While I acknowledge my immense privilege of being an educated, light-skinned woman from a liberal home, my life is also shaped as a female Indian immigrant to Canada. I had only experienced my positionality through these rigid categories: as oppressed from being Indian, or powerful from being light skinned and educated, I had never thought of myself as powerful for being Indian before.

In Decolonizing Methodologies, Linda Tuhiwai Smith writes that “research is inextricably linked” to colonialism and imperialism (Smith, 1999, p. 2). Just because I am Indian does not mean my research in Nepal is automatically separated from colonialism and imperialism. In fact, India practices its own form of imperialism in Nepal through political meddling and influence, and my understanding of Nepal through comparison with India may serve to contribute to this imperialism in my research. This experience made me better understand my position as a woman who is powerful in some contexts, less powerful in others, through my South Asian identity.

3. Navigating my Indian identity in another South Asian context was an entirely new experience that allowed me to better understand my positionality and engage in the most in depth reflexivity I have ever practiced.

Kim V.L. England writes of reflexivity, stating that it is “self-conscious analytical scrutiny of the self as researcher” which can “[induce] self-discovery and lead to new insights and hypotheses about research questions” (England, 1994, p.244). Being in Nepal as an Indian woman added a level of nuance to my positionality and provided me with deeper understanding of myself in general, and also as a researcher.

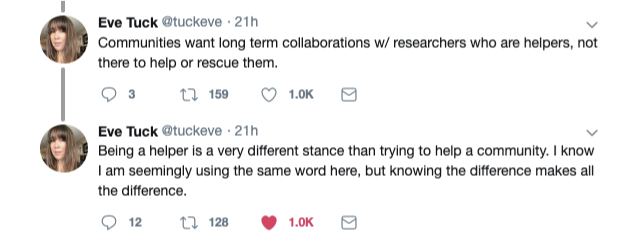

Shortly after we returned to Edinburgh, Canadian Indigenous academic Eve Tuck tweeted about research in topics that locals and/or Indigenous communities do not want, or be studied. She also wrote that researchers must be “helpers” to communities in which they study and not “rescuers” (Tuck, 2019). These tweets were written at what seems like a cosmic time- I realised that although I was South Asian, that was not the golden ticket to access all South Asian communities. In fact, I must often be a helper because I am not from every single South Asian community- they are unique with varying wants and needs.

(Source: Eve Tuck, 2019)

During the end of our trip, we took part in small research projects conducted through fieldwork. My learnings and new layered understanding of my positionality helped me realise that although I am South Asian, I cannot speak for anyone, similarly to my non-South Asian teammates. We created open- ended questions about textiles and waste management and especially asked “What do you need to better manage textile waste?” We wanted to ask questions that would produce answers that actually matter to communities in Kathmandu without assuming what is needed, particularly assumptions influenced by my experience of India (Tuck, 2019).

On Community and Validation

I also found that my South Asian identity was validated in Nepal.

1. I have always struggled with a “hybrid identity,” feeling too Indian in North America, and too Canadian in India. While being in Nepal gave me a deeper understanding of the power that may come with being Indian in the South Asian context, it also gave me a deeper understanding of myself as an Indian woman in general.

Growing up, on visits to India, I was delighted when people knew I was Indian, rather than a foreigner, but this was a rare occurrence. Often, I was too foreign.

Our first night in Kathmandu, we met Kaustuv Raj Neupane, programme coordinator at the Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies (SIAS), a think tank collaborating with our programme. During dinner, Kaustuv asked me where I was from. Self-conscious about having my Indian identity disputed, I replied “I’m Canadian.” Kaustuv replied, saying I looked as if I were Indian. I immediately messaged my boyfriend, who has been witness to my hybrid identity , in excitement. Kaustuv and I went on to discuss India, Nepal, South Asia and North America .

More people around Kathmandu asked if I was Indian. Suba, a woman working at the hotel whom I interviewed during our fieldwork cried after our five-minute conversation, telling Kaustuv in Nepali that I reminded of her beti.

Banita Khadka, a SIAS volunteer and our partner for our fieldwork project, and I bonded over our love for Bollywood and shared words both in Hindi and Nepali (like chappal, meaning sandal). She excitedly recommended a Bollywood film to me, a few days into our trip on the way back to our hotel in Dhulikhel. Namastey London. “It’s about an Indian girl who moves to Britain. It’s like you!” she said, validating my hybrid identity. I watched the film on the flight back to Edinburgh, with feelings of acknowledgment.

The two lessons I learned about my identity are at odds with one another: South Asian identity is diverse, and I can never assume to be knowledgeable, only act as a helper. Yet, there are points of similarity. This experience made me understand how to navigate that cautiously, sharing cultural elements with communities but knowing I am from hegemonic force in South Asia.

On Kindness, in life and in research

Sometimes it is so easy to get caught up in doing things competently and achieving high standards that it can be difficult to remember that being pleasant, curious and kind goes a much longer way. Throughout my time in Nepal, I learned more and more about kindness, both obvious and subtle, while interacting with our collaborators at SIAS and other Nepali locals.

1. Banita, at first a collaborator, now a friend, helped us with our fieldwork on day ten of our fieldtrip. She worked with us to conduct interviews with locals on the street and organisations in various neighbourhoods of Kathmandu, including Senapa, acting simultaneously as a translator and teammate.

Banita moves with warmth. Every interviewee with whom she interacted was visibly drawn to her kindness and joy. My group, which included colleagues and friends: Brigitta Bence, Amelia Roberts, Sarah Roper and Megan Todd, initially discussed our interviewees’ participation with Banita, in awe of the interactions she had and understanding it as her utilising her local, Nepali connection. We later realised it was also because of Banita’s kindness. She greeted each and every person with a soft familiarity- not the uncomfortable kind that could spur feelings of mistrust, but a genuine care for, and playfulness with the person with whom we were interviewing.

Banita was the same with us. Though the pressure of arranging interviews, running around Kathmandu to meet specific people and creating a presentation on Google Slides without access to internet contributed to some tense moments, we still had fun, enjoying an intimate camaraderie amidst the chaos. After presenting the project to our peers, mentors and collaborators, we concluded that it went well not only because our research was good, but also due to the fact that we enjoyed being around one another.

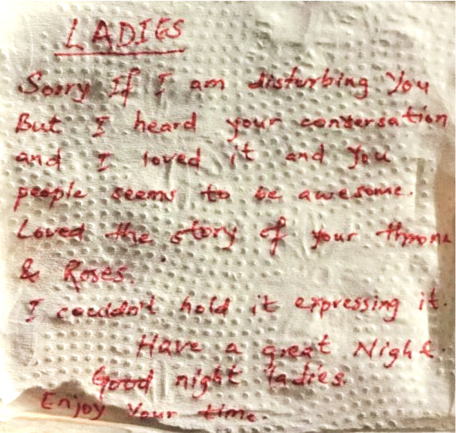

2. One night, friends and I were sitting at the Blue Note Café in Sanepa near the Yellow House. I asked them if they would like to play “rose and thorn.” We would go around and say the best and worst moments of our field trip, laughing hysterically at beautiful moments and groaning in solidarity at the mention of various ailments we experienced. A young man sitting across left us a note without saying anything, writing:

Photograph of Napkin with Note on it, April 20th 2019

This young man simply wanted to share some knowledge of his happiness, in hopes that it would also make us happy. He did not want anything from us. I believe one can look at research and collaboration this way, as sharing something without taking anything away.

Upon returning to Edinburgh, I was discussing an upcoming job interview with a close friend’s sister. The sister had recently graduated from medical school and offered me advice she deemed the most crucial: be the 3 am partner. Meaning, if you were to work a 3 am shift in a busy emergency room, be the kind of person with whom people will want to be partnered. Travelling to Nepal has given me a deeper appreciation for this in terms of research and fieldwork. Be a good partner. Be a helper. Be supportive, be kind.

Published on 2019/10/21